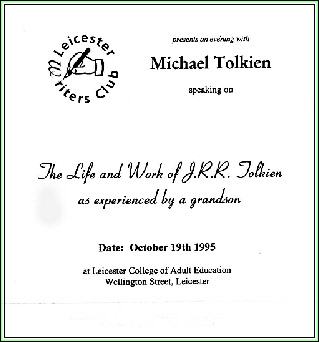

Autobiographical essay on my grandfather,

J.R.R. Tolkien,

based on a public talk* requested by

The Leicester Writers' Club at

College of Adult Education, Wellington Street

October 19th, 1995.

Notes:-

1.)Longer excerpts, which are merely alluded to or digested, were actually read out in full.

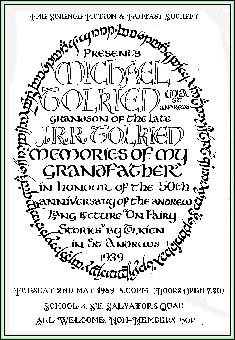

*2.) This talk was composed on the basis of my lecture given in April 1989 at St Andrews University, at the invitation of its Science Fiction and Fantasy Society. In a sense it commemorated my grandfather's Andrew Lang Memorial Lecture of 1939. But there have been many additions and stylistic adjustments, as well as omission of more pointedly 'academic' materials. (Click to see the full text of this lecture)

¶1...' My name is TOLKIEN ( not _KEIN). It is a German name from Saxony, an anglicisation of Tollkiehn ( that is tollkühn) But, except as a guide to spelling this fact is as fallacious as all facts in the raw. For I am neither foolhardy { as the name implies} nor German, whatever some remote ancestors may have been...' These are not my words, and only about me as accidental inheritor of that name. I am quoting from my grandfather's notes to his American publishers after a N.Y Times book reviewer made some fatuous assumptions. It has the combative and punctilious flavour of much that he said and did, anticipating what I would like to celebrate.

¶2 I was always made to feel from my parents' exaggerated accounts that I came

into the world on indirectly bad terms with my grandfather, though I did become a

source of reconciliation. He and my grandmother had disapproved of my father Michael's

hasty wartime marriage to my mother who was one of many nurses he fell in love with

when he was being treated for the shell-

¶3 All this had really been brewing for years. My father's unpublishable autobiographical

attempt to make sense of and to some extent idealise the conflicts and confusions

of his childhood reveals that he felt an obsessive need to establish belief in himself

and to secure his parents' attentions. I recall him saying bitterly that he was

once told in one of his rebellious moments that his not being a girl was a disappointment

to his parents. He also told me proudly that he walked out after one of those disputes

that isn't really about the issue at stake, and on the eve of the'39-

¶4 I am often asked if it's a nuisance to have a name so unusual that I can't escape from the inevitable curious comments. I hope that what I am going to say will be a kind of answer to this; but I also hope that it will provoke you into asking questions later on.

¶5 I shall avoid the kind of anecdotes I started with. Simply to relate experiences

has the danger of becoming sentimental, self-

¶6 When the American edition of Carpenter's biography came out, one critic said

it had neglected to tell us all we would like to know about Tolkien the man in his

mature years. I can only begin to take up this challenge and wherever possible I

have tried to objectify memories and impressions by referring to letters and to my

experience of him as it emerges for me from the actual works. I am also going to

be quite specific about my grandfather's impact upon me at certain formative periods

of my life: for example, I was obliged to study Anglo-

¶7 My literary training makes me acutely aware of certain critical trends, which I will touch on both because they have affected the way that Tolkien's life and works have been viewed in some quarters and because I hope my approach may suggest how to steer a middle course between various extremes.

¶8 First the 'biographical fallacy': know your author intimately and you have

an 'open sesame' to his works. Tolkien himself anticipated this as early as 1935

in a letter to W.H.Auden, where he talks about the great spider Shelob ( successor

to Ungoliant, co-

¶9 I think I am also echoing my grandfather's feelings if I touch on the critical tendency of looking for watertight theories about the works, reading in references to world or contemporary history on the assumption that Middle Earth is 'real'. Critics are seldom content to say 'this is what x suggests to me'; responses turn into hard and fast interpretations. Even worse vast significance is attached to what's NOT in the books. The author himself disclaims inner meanings and messages in his own foreword to the L/Rs; but in 'Tree & Leaf' he talks about the creator of fantasy achieving an 'inner consistency of reality', a world inherently believable on its own terms. So perhaps he became the victim of his own success in doing this. He certainly always maintained that he was exploring rather than inventing the legends accredited to him. His imaginative world became so vast that much of it was imponderable to its conceiver as the unfinished and perpetually developing Silmarillion suggests.

¶10 The way to keep a clear perspective on the apparent clash between two kinds

of 'reality' (imaginative and literal) is to look at the literary means by which

he brought his imaginative world into being and the preoccupations of the mind that

created it. My Uncle Christopher's scholarly tracing of the entire literary and imaginative

history of the Ring in twelve volumes is now an indispensible part of achieving an

assessment on appropriate lines. And I hope this talk will help to demonstrate how

both biographical material and well-

¶11 My memories of him as philologist are of prime importance in this respect.

The literal meaning of the Greek is 'love of words': I draw attention to this to

dispel ideas of him as a kind of talking dictionary with dry expertise about derivations.

There's revealing detail from the time when he was studying for a crucial part of

his degree in 1912: he discovered in Exeter College library a Finnish grammar and

years later told W.H.Auden: '...it was like discovering a complete wine cellar filled

with bottles...of a kind and flavour never tasted before. It quite intoxicated me...'

(in fact he nearly lost his exhibition award and got sent down or so he said.)'...

and I gave up the attempt to invent an unrecorded Germanic language and my own language-

¶12 Later he became an authoritative linguistic scholar; but he always gave me the impression that words, in an almost physical sense, have a special kind of life to be pondered, savoured and probed. I recall family occasions, usually meals with cross currents of chat. He had the ability to carry on several conversations at once, debating the merits of a recipe, exploding wrong theories about a place name, telling anecdotes about an eccentric character and under his breath trying to solve a linguistic matter that had arisen unnoticed by anyone else. In my imagination he became the ultimate authority on the origin of names and the uses and abuses of words. He would expose common assumptions so rapidly and overwhelmingly that you were compelled to listen and agree. But he also respected words that were perplexing and he delighted in their elusiveness. When he became involved in linguistic matters to do with his own works he proved particularly sharp in disabusing theoreticians and critics of their misconceptions. Two letters in the Carpenter selection illustrate this amusingly. There's too much to quote; but I warmly recommend his analysis of a Daily Telegraph Magazine interview in 1967 and of the introduction and appendices to the Swedish translation of L/R.

¶13 When I was an advanced student of mediaeval and Anglo-

¶14 Before discussing more closely links between the philology and the fictional

works I would like to mention a few more anecdotes:-

1. I remember sitting with him in hot August sun, a month before he died and watching butterflies on a buddleia bush. He told me in great detail how the word butterfly was etymologically a dead end: noone had ever discovered how or why the two words had been associated; the displacing of sounds in flutterby wouldn't do, either. As usual I found that any word he discussed took on a new dimension and so did the object it was attached to.

2. When my first daughter Catherine was born in 1969 he was very concerned to explain in a long letter all the vagaries of spelling attached to this name: ' I meant to have a say over the matter of my great granddaughter's name...and now it's settled; but I meant to support you in CathArine...' A lengthy philological discussion followed, typically sandwiched between all kinds of mundane matters. But his enthusiastic command of detail compelled one to read on and to learn. ( Incidentally, one of my memories, happily preserved in a photograph, is of his entertaining his three year old granddaughter with excerpts of the Tom Bombadil poems. As ever he had a natural and spontaneous gift for striking an answering note in children.)

3. He always thought highly of Jonathan Swift, less for the ingenious and biting satire which he probably felt relied too heavily on allegory, than for inventing a new sound in the language by using the word Yahoo to describe the humanoid apes of Gullivers Travels, book IV.

4. When I was 14 he wrote me a letter which illuminates his wide-

'...on the strength of the L/R, I suppose: a pleasant compliment and pat of approval,

and one which few if any philologists or language men have received...' Another of

the many indications that he saw the book as an offshoot of his linguistic interests:

something many critics would do well to ponder. He talks about supervising the Dutch

edition and translation of the book and how he's immersed in a study of Hebrew: '...if

you want a beautiful but idiotic alphabet, and a language so difficult it makes Latin

or even Greek seem footling but also glimpses into a past that makes Homer seem recent-

¶15 It was only when rereading The Hobbit and the L/R after my intensive linguistic

studies at St Andrews that I began to appreciate and find delight in the connections

between Tolkien's philological skills and wisdom and his fictional work. I was lucky

to see a great deal of him during my subsequent B.Phil studies at Oxford; and knowing

how beset by pundits and enthusiasts he had become I was scrupulous about not bothering

him with the many linguistic questions that reading the books had provoked; but this

was probably a mistake since his correspondence with me and many he never met reveals

a generous, professional concern to examine the derivations and etymology of the

names with their attached legends in the books. For instance I had been pondering

over the name Mirkwood in The Hobbit and wrote to him about this: did it mean as

in the Anglo-

i) every authority mentioned involves a legendary or historical association which enriches the meaning or feeling of the word; ii) as often he felt he was working with material which was part of a huge body of verbal/historical/ mythical lore, the keys to which could only be found by perplexing labour and might even evade you when you thought you were getting close. (It's not surprising that he read detective fiction for relaxation and went out of his way to praise Agatha Christie.) iii) As he always contended, The Hobbit was 'a fragment torn out of an already existing mythology'(Reply to N.Y Times Book Review inquiry of June 1955)

¶16 It is interesting here that he says that it was great good fortune that Mirkwood

remained intelligible with exactly the right tone in Modern English. He always said

to me that names had the power to generate a story for him. It is well-

¶17 Characteristic of my grandfather's lively methods of enquiry and often quizzical pursuit of detail is the moment in the 4th chapter of the Two Towers where the ent, Treebeard, and Merry and Pippin discuss their names and origins. I refer to the passage beginning: 'Pippin, though still amazed, no longer felt afraid...' and ending where Treebeard declares: " Real names tell you the story of the things they belong to in my language, in the old Entish as you might say. It is a lovely language, but it takes a very long time to say anything in it, because we do not say anything in it, unless it is worth taking a long time to say, and to listen to." Treebeard is almost a ponderous pedagogue, but suddenly his alliterative, rhythmic search for the key adds new dimensions to the enquiry; and Pippin's adding a new line in similar style is the kind of solution to a textual omission that Tolkien had provided in his scholarly work at editing poems like Sir Gawayne & The Green Knight. At this moment we almost expect an analysis of the term hobbit; but with narrative tact the author allows the ent's more intriguing lore of names and stories to predominate. And what Treebeard says of names telling stories indicates one of Tolkien's creative mainsprings.

¶18 It is therefore worth noting that after my Uncle Christopher had been lecturing on the heroes of northern legend at St. Anne's College, Oxford, my grandfather said to him in a letter: 'I am a pure philologist. I like history...but its finest moments for me are those in which it throws light on words and names...Nobody believes me when I say that my long book is an attempt to create a world in which a form of language agreeable to my personal aesthetic might seem real...' And when W.H.Auden was due to talk about the L/Rs on the radio in June 1955 Tolkien wrote and told him that :'...Languages and names are for me inextricable from the stories. These are an attempt to give a background or world in which my expressions of linguistic taste could have a function. The stories were comparatively late in coming...' (Both letters are in Carpenter's selection.)

¶19 He loved riddles, posing puzzles and finding surprising solutions. Riddles

have rules. They are an art form in Anglo-

¶20 It's apt to round off focus on Tolkien as a philologist with some excerpts

from 'Tree and Leaf', the essay on Fairy Stories, and in particular where it focuses

on Fantasy. First to show his insistence that the powers of language and story-

‘... Anyone inheriting the fantastic device of human language can say the green

sun. Many can then imagine or picture it. But that is not enough-

To make a Secondary World inside which the green sun will be credible, commanding

Secondary Belief, will probably require labour and thought and will certainly demand

a special skill, a kind of elvish craft. Few attempt such difficult tasks. But when

they are attempted and in any degree accomplished then we have a rare achievement

of Art: indeed narrative art, story-

(He goes on to say that the truest Fantasy is achieved by words; what passes for such in painting or drama is fundamentally different, and by misguided association demeans the former art.)

¶21 My talk is partly intended to indicate aspects of the author's interests and concerns which I believe are easily overlooked; but I am also trying to illustrate what it was like to be his grandson; so I am going to introduce some of the more random aspects of his personality. A reference to his own ingenious fairy story, Leaf by Niggle, serves both my purposes. By 'fairy' here we should perhaps understand 'strange enchantment'. The title refers to a single leaf sketch left over from a painting of vast ambition and scale and never finished. It was written at the same time as he was composing the essay I have just quoted from and published along with it in 1947.

¶22 We can read into it some of his confusion as to what direction his ambitious

and increasingly daunting saga of the Ring might take; but I am going to look at

a few parts that sum up some aspects of his behaviour as I knew them. Niggle's conflict

between absorption in his art ( the status of which he is unsure) and his kindly

sociable heart was something I noticed in my grandfather's conflict between the life

of the study and other unavoidable daily distractions. His study felt like a sacred

precinct to children of both generations, though he himself might often hate it and

curse it, feel worried about becoming too buried in it, and yet feel compelled back

to it. Niggle is no more precisely JRRT himself than Bilbo is, though there are reflections

of him in that particular hobbit's reluctance to be dug out of his routines behind

the Shire borders by Gandalf's crazy proposals. The opening of Leaf by Niggle reveals

a similar theme: ' There was once a little man called Niggle, who had a long journey

to make. He did not want to go; indeed the whole idea was distasteful to him; but

he could not get out of it. He knew he would have to start sometime, but he did not

hurry with his preparations.' Tolkien's ability to achieve some kind of resolution

of the conflicts between his inner life, his professional duties, family demands

and other sociable activities is part of his stature as a man and reflects the humanity

we find in the most endearing of his fictional heroes. He was by no means the absent-

¶23 Ironically, though, Tolkien was to be persecuted far more by those bursting

to be informed about every vein and particle of his 'leaves'; and I think he liked

the world's Tomkinses and Atkinses better than those who cross-

¶24 Unlike Niggle, Tolkien was not just puzzled by bureaucrats and officials who pulled their rank on him: he loathed them though he could often win them over with genuine courtesy which came from forgiving them for what they stood for and seeing them as people. Then he would boast about how he'd won them over and sing their praises. Like Jonathan Swift he found humanity hard to bear but had a love for individual Jacks and Jills. Writing to me when I was on holiday with my family on the edge of Dartmoor in 1957 he said: '...I should have loved to have been with you on the high Tors and away from people, that is folk in the mass...' He always maintained that he was affable but unsociable. Most readers of his work now realise something that soon dawned on me from all this: he was fascinated by the miraculous capacity of small and insignificant people (like H.G.Wells's Mr Polly) to achieve the unexpected in face of apparently insuperable odds. He said quite openly that his time in the trenches in the Great War stamped this feeling on his imagination. Two excerpts from Elrond's words at the Council in the Fellowship of the Ring are powerful reminders of this: I remember him quoting the first one on a radio interview:

' This quest may be attempted by the weak with as much hope as the strong. Yet

such is oft the course of deeds that move the wheels of the world: small hands do

them because they must, while the eyes of the great ones are elsewhere.'.....'This

the hour of the Shire-

¶25 It's reasonable to infer from these unpatronising and unsentimental comments

by Elrond a crucial and central theme in his major works, even when the protagonists

are in the guise of semi-

¶26 However, it was always difficult to keep track of his views, which might modify or intensify without warning, my grandfather had his feet firmly on the ground. This 'earthed' quality is reflected in the precision of geography and time scales of his major work, from which researchers and graphic artists have made much capital. He is even reputed to have been expert on the habits and features of the house sparrow and gave a paper to an ornithological society. If he had an enthusiasm for a person, place or gadget, an item of food or drink

( never French !) he could always defend his preference; but weeks or months later

you might find him demolishing it just as persuasively. Both his children and their

successors would agree that it was possible to pass in and out of favour without

knowing it if you happened not to have visited my grandparents' home for some while.

But looking back I think these eccentricities added to the affection I felt for him;

and I was more likely to follow his advice than that of my parents even though it

wasn't necessarily any better. He had a way of making me see the real world of living,

breathing and often inexplicable things in a new light. In 'Tree & Leaf' he maintains

that such reappraisal of the familiar is achieved in a well-

¶27 I have said that in balanced critical terms Tolkien should not be identified

absolutely with Niggle or Bilbo or for that matter Frodo or the just but fallible

heroes of The Silmarillion; but I have always found something of my grandfather in

the stories: innumerable shades of attitude and tone in hundreds of details of course,

but particularly in the figure of Gandalf who is as vital offstage as when he's central

to the action. In The Hobbit his presence in the dialogue and narrative is small,

and in The Lord of the Rings members of the fellowship are either waiting for him

to show up or frustrated by his absence; overjoyed, too, when he returns as Gandalf

the White after having won what always seems the fatal tussle with the Balrog of

Moria. Tolkien had just this very kind of ever-

1.) Gandalf takes the view that life is inevitably an adventure not a series of easy routines and that each traveler is of vital importance in some mysterious way. How is for them to find out, though he'll guide them periodically if unpredictably. This is the authorial voice embodied in an authoritative figure but never too obtrusively.

Just before Bilbo and the dwarves encounter the trolls...'they noticed that Gandalf was missing. So far he had come all the way with them, never saying if he was in the adventure... he had eaten most, talked most, laughed most. Now he simply was not there at all...' There's similar outrage just before they enter Mirkwood after enjoying the hospitality of Beorn. They sense that he is about to leave them and receive sharp words about taking responsibility for their own expedition.

(See The Hobbit, p.119 ) I find here all the unpredictable reliability and the rather irritable kindness of Tolkien. I would react as the party did with a mixture of exasperation, affection, need and respect. It also reminds me of how he could exert authority and influence without domineering. Gandalf like him also understated what was of huge consequence in his own business, which is at least indirect evidence that The Hobbit was only a fragment of a much larger concept and emphatically not the starting point of his imaginative world as many continue to suppose.

2.) In the first of these excerpts we see Gandalf's relish for fun and the good things of life. His tricking of the trolls into arguing beyond the dawn that transformed them to harmless stone and later on his tossing of lighted fir cones at the warg wolves also illustrate this aspect of my grandfather: one of my earliest memories ( I was 7 or 8) is of a long family walk down overgrown lanes in the wooded Chiltern Hills north of Reading where I was lucky to be brought up before the district was 'developed' into dormer villages. Hedgerow hemlock and hogweed were in flower; he called their white inverted umbrellas 'wasps' tables', and constantly upset these predators by dashing in with his stick and slicing off a table, telling us to run for it. It made us hysterical with excitement much to my mother's silent irritation. We also delighted in a game where he threatened with all kinds of murderous and menacing gestures to catch us with the hooked end of his stick. The stick, mischievous as Gandalf's wand, was part of one of his funniest stunts: a loud "HOI !" and violent waving at motorists hogging country lanes as if they owned them. In the same vein but years later, when he was 81, I remember him racing my then four year old daughter Catherine round the great lime trees of Merton College gardens.(This was on the occasion when I took the last photograph of him leaning on his favourite tree, included in the illustrations of Carpenter's biography.)

3.) Another aspect of Gandalf I connect with Tolkien is in the hidden dimension. Like the craggier Dr Who impersonators he might seem at times to be rather old, tired, frail, battered by the demands of a perverse world. His elvish name is Mithrandir (the grey pilgrim); but he was a Maia, one of the ancient Istari or wizards. In The Two Towers he comments on his former stature:

' Olorin I was in my youth in the West that is forgotten.' In The Hobbit and the

L/Rs his deep wisdom is disguised, a powerful irony against his enemies. He seems

just persuasively managerial towards Bilbo and the dwarves until his spirit towers

into authority and halts the advancing dwarves of the Iron Hills at the Battle of

the Five Armies.( See The Hobbit: pp 233-

4.) Like Gandalf, too, my grandfather delighted in winning without being boastful about it. He had a knack of mastering techniques at lightning speed and dumbfounding the experts because he could genuinely play at lighthearted things. I recall endless rounds of clock golf with him at the Hotel Miramar in Bournemouth and his delight in successions of 'holes in one' as if they were quite natural to him. This winning capacity is captured for me where Gandalf explains to Thorin why he kept the map, explaining to the astonished dwarf company that he had visited their leader's father in the dungeons of the Necromancer. '...I was finding things out as usual; and a nasty, dangerous business it was. I tried to save your father, but it was too late. he was witless and wandering, and had forgotten almost everything except the map and the key.' ( See The Hobbit,p.32)

¶28 But now I can hear Bilbo urging on Gollum in the subterranean lakeside riddles

test with "Time's up !" Like him, too, I'm trying to sound bold and confident; but

like Gollum I'm going to cheat by working in several other items at once, including

other crucial parts of my memory and experience of Tolkien I would like to have covered:

his love of the family unit and his vital role as its head and keystone; our mutual

interest in and love for the Welsh language, on which the Sindarin tongue, a Grey-

¶29 Trees demand a last digression. If I were asked to read from a work not sufficiently

acknowledged it might be a passage from his translation of Sir Gawayne & the Green

Knight. He composed it in a modernised form of the original mid-

¶30 I suppose I could have dealt with many of the adverse criticisms of his work but I prefer to end positively with my own estimate of the quality and continued popularity of Tolkien. People of all ages like the books because the tales adjust themselves to who you are when you are reading them, so there is always something new to discover. A quality he defines in 'Tree and Leaf':'...I doubt if...the enchantment of the effective fairy stories...becomes blunted by use, less potent after repeated draughts.'( See Tree & Leaf,p.38.) But much of the appeal lies in the complete and consistent imaginative world, which includes characters and situations with which we can identify without being bombarded by messages and engineered layers of meaning.

¶31 The books are 'classics'. Up-

¶32 Significantly, he disliked most modern attempts to rewrite or even reinterpret old materials: he felt they led to uncertainties of tone or spirit.

¶33 In his stories he returns us in an accessible way to what the psychiatrist and polymath, Jung called the 'archetypes', the mythical patterns that lie buried in us from the long human quest for the truth about who we are and why we are here. Pippin's attempt to recall the ent Treebeard's eyes captures this subconscious mythical impact: '...behind these eyes ', he says he felt ' as if there was an enormous well, filled up with ages of memory and long, slow, steady thinking; but their surface was sparkling with the present: like sun shimmering on the outer leaves of a vast tree or on the ripples of a... deep lake.' ( Such intuitively profound insights into perspectives of history were moving to Tolkien, and he found his characters surprised him with them.)

¶34 For me personally he himself was one such 'archetype', as I hope my talk

has implied. His death in September 1973 first made mortality real to me. I'd lost

other loved and close relatives; but his passing removed a centre of gravity, a source

of unity, a formative influence I am still piecing together 22 years later. His uniqueness

can be no better distilled for me than in these words from The Silmarillion:-

'...In that time the last of the Noldor set sail from the Havens and left Middle Earth for ever...'

.